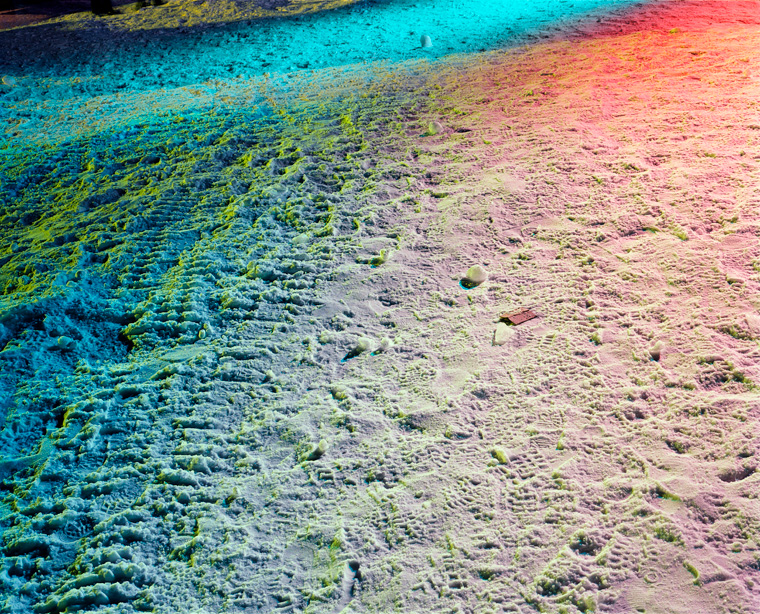

Spectrum 1A, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm

Spectrum 1A, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm Spectrum 1B, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm

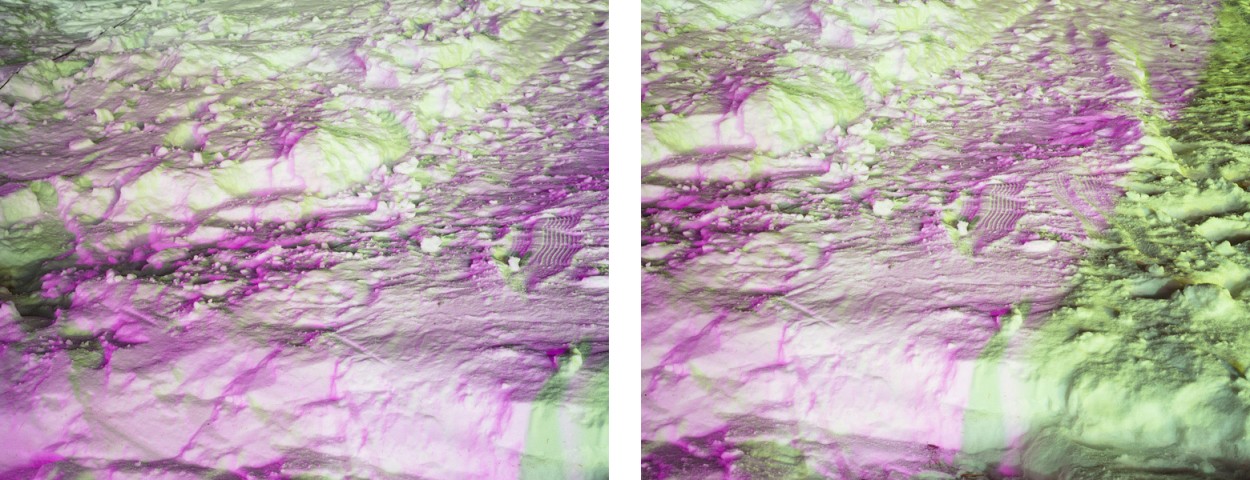

Spectrum 1B, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm Spectrum 3A, 3B, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm, each

Spectrum 3A, 3B, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm, each Spectrum 7A, 7B, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm, each

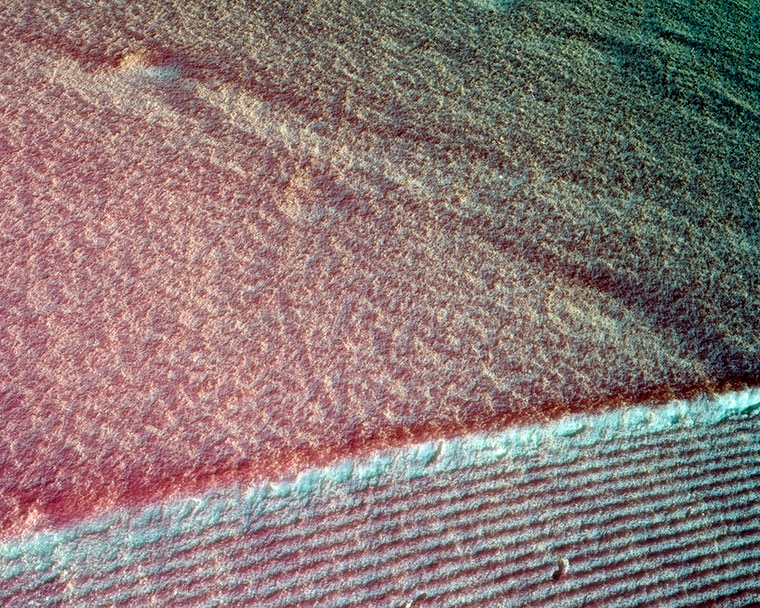

Spectrum 7A, 7B, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm, each Spectrum 5, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm

Spectrum 5, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm Spectrum 7, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm

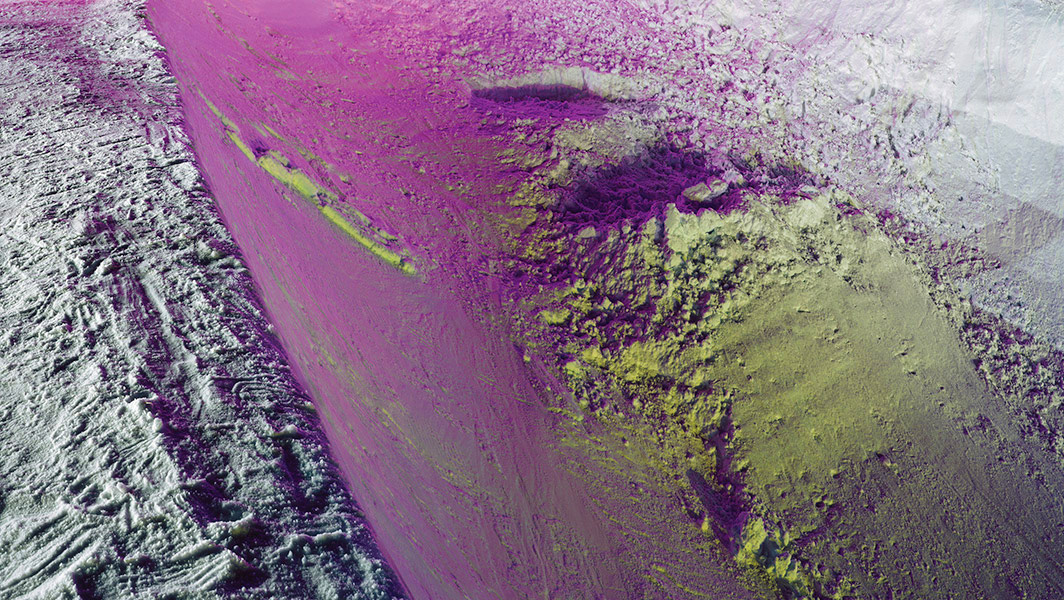

Spectrum 7, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm Spectrum BM, 2008, c-print 110 × 180 cm

Spectrum BM, 2008, c-print 110 × 180 cm Spectrum BDEEP, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm

Spectrum BDEEP, 2008, c-print 100 × 125 cm

Of white snow

Virgin fields of white. Dark pine trees, whose snow-laden branches bend under the weight of their powdery load. Here and there a wooden hut among the undulating hills, surrounded by a backdrop of massive mountain rock. The idyllic picture of an alpine winter landscape – as seen on picture post-cards and tourist industry advertising brochures. Snow as a symbol of purity seems to be the ideal advertising medium; a positive, creative image based on the idea of unspoiled nature, the same nature that in the 19th Century attracted the first tourists from England to the alps during the summertime. Yet even for the Kabbala, snow is a symbol of dichotomy that on the one hand conveys purity and growth, while on the other destruction, just as it embodies the potential for evil. And no one knows this aspect better than the inhabitants of the mountains themselves. continue reading >>

Jules Spinatsch’s series of pictures ‘Snow Management’ unveils in a stunning way exactly this ambivalence. Already in the chosen title, which unifies material and infrastructure in a succinct way, a contemporary conception of the relationship to the natural elements is highlighted clearly. Today snow is a natural element which in order to allow a coexistence with mankind and his civilisation, requires both control and creativity. This is not only to prevent natural catastrophes and to allow for mobility but also because snow can represent an important economic resource. Its purity is only a superficial requirement – it is the seductive aspect of a product whose raw material can even be (re)produced by means of high-energy expenditure.

Snow can be a highly photogenic subject, perhaps even a photographic challenge. Coping with whiteness is no easy task and requires a great deal of technical know-how. Spinatsch sets the accent in his pictures not only on spectacular light contrasts which the snow allows for but also concerns himself with the problem of natural elements and the functional technology to which they are subordinated. During the winter the photographer visited the most famous winter resorts to take his pictures. There, where provisional arenas for classic wintersports competitions are set up, the incongruousness is at its most visible. The natural landscape is reinforced with – as Spinatsch puts it – Alpine Units, clearly provisionally built installations which as a result of their material form possess sculptural aesthetic characteristics, as they have to look safe and beautiful when transmitted as television images, at least from the perspective captured on camera. This results in a hybrid situation in which nature and technology, material and function clash, yet – at least temporarily – appear to accommodate one another. The aesthetic brute force that these functional elements release in nature finds a balance in Spinatsch’s pictures as well as a logical, sometimes uncann, identity.

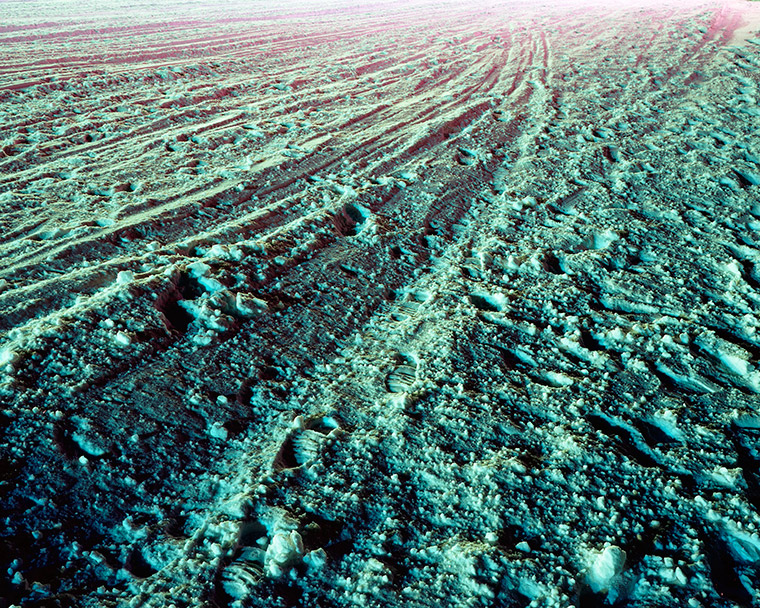

As well as the Alpine Units, the artist defines other pictures in the series as ‘Applied Landscapes’. Here the modelling of the landscape itself is the central focal point. These pictures are reduced to a virtual form of basic black & white classical photography and present freshly prepared ski slopes, functionally lit at night by lamps from snow vehicles or snow canons. The keen sharpness of these clips, and the minimal chromatic play that arises on the snow surface, put these landscapes into a state of suspension which, like science fiction imagery, lies somewhere between reality and fiction. The artificiality of this formed nature is highly tangible.

‘Snow Management’ reveals the un-blemished purity of snow. Visible are the traces of scattered salt and other chemicals, the flatness of industrial snow crystals and the marks left by the trails of snowcats. The snow of an alpine sport landscape, which our pleasure-seeking society needs and exploits, could just as well be green. As green as a golf course.